The General Rules

Here at Cogent Legal, we create visuals that help you tell your client’s story as clearly and persuasively as possible. But as former litigators, we also understand that creating the visuals is only part of the battle – you also need to be able to use them. We continually ask ourselves not only what we can do to make your visuals as compelling and beautiful as possible, but also what we can do to make sure they are admitted.

We also like to assist our clients in understanding how they will be able to use their exhibits, so that they make this part of their overall strategy. So we periodically publish guides on the relevant rules.

In this post, we focus on the general rules that apply to demonstrative exhibits in Washington State courts, in recognition of the opening of our Seattle office. In coming posts, we will discuss some common pitfalls and tricks for avoiding them, in Part Two: Relevance, Hearsay, and Foundation, and Part Three: Experts, Summaries, and Using Visuals Early in Your Case.

What is demonstrative evidence?

This seems like a simple question, but there is an important distinction between demonstrative evidence and foundational, or substantive, evidence. Different standards apply to these different types of evidence.

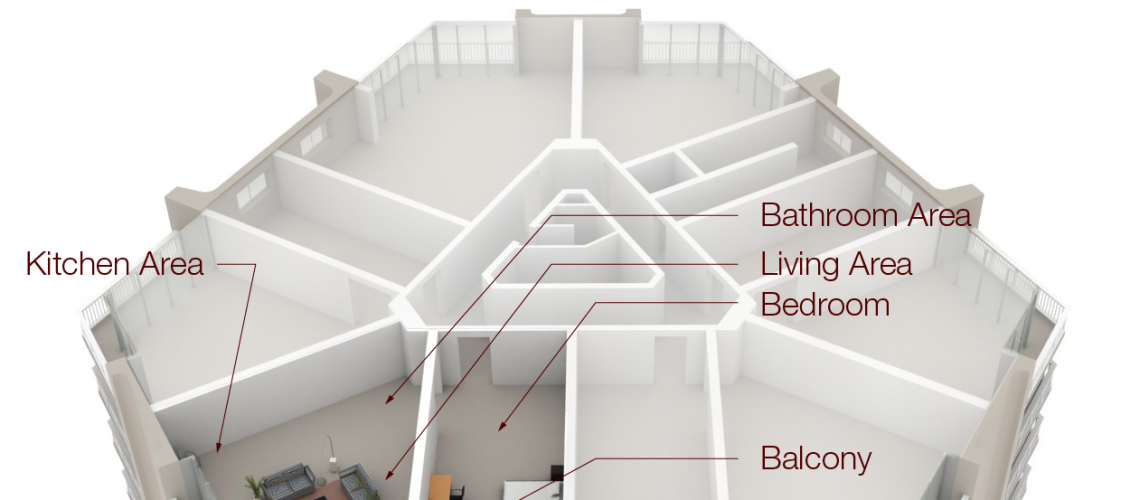

Generally speaking, demonstrative evidence designed to “aid the trier of fact in understanding other evidence.” State v. Lord, 117 Wash. 2d 829, 855 (1991) (emphasis added). This includes things such as diagrams, timelines, animations, summaries of already-admitted documents or testimony, and charts.

One reason this distinction is important is that a jury can view demonstrative evidence during trial but cannot have a copy of it with them during deliberations. In re Woods, 114 P.3d 607, 622 (Wash. 2005); Lord, 117 Wn.2d at 856-57.

You also cannot prove a case with demonstrative evidence alone. Demonstrative evidence, done well, streamlines your case and makes it more compelling, but it will never replace the evidence it is based on. This is an especially important distinction for experts (as we will discuss more in Part Three); if your expert relies on a diagram or an animation to form an opinion, rather than simply using it to illustrate an opinion, that evidence will face a higher bar for admission.

However, once you have this distinction in mind, and know how you will be using your evidence, the standard for admission of demonstrative evidence is relatively simple to meet.

Washington courts favor and encourage demonstrative evidence.

In Washington, demonstrative evidence is not only admissible, but encouraged. See, e.g., State v. Finch, 975 P.2d 967, 984 (Wash. 1999) (“The use of demonstrative evidence is encouraged”); In re Woods, 114 P.3d at 621 (“The use of demonstrative and illustrative evidence is to be favored”).

The test for admissibility is, overall, not onerous. Put simply, your demonstrative evidence cannot be misleading. Put technically, the evidence must “enlighten the jury and to enable them more intelligently to consider the issues presented,” it must be more probative than prejudicial, and depictions of evidence or scenes must be substantially similar to what they seek to depict. See, e.g., Finch, 975 P.2d at 984; Lord, 117 Wash. 2d at 855-856 (Wash. 1991).

Further, demonstrative evidence does not have to be an identical representation of the facts, as long as it is substantially similar to what it is depicting. See, e.g., Finch, 975 P.2d at 984-85; Jenkins v. Snohomish County PUD, 105 Wash. 2d 99, 107 (1986); State v. Hultenschmidt, 102 P.3d 192, 197 (Wash. App. 2004). Assuming there is substantial similarity, any differences go to the weight of the evidence, and not its admissibility. See Jenkins, 195 Wash.2d at 107.

If you have carefully crafted your demonstrative evidence, you should not have difficulty getting it admitted. But there are a few details to keep in mind, which we will cover in our next blogs on this issue, Part Two: Relevance, Hearsay, and Foundation, and Part Three: Experts, Summaries, and Using Visuals Early in Your Case.

At Cogent Legal, we are ready to help you navigate these rules and get your demonstrative exhibits admitted at trial. Our goal is to never create a demonstrative exhibit that our client cannot use. You can reach Tyler Weaver, Executive Director of our Seattle office, at 206.816.5128 and tyler.weaver@cogentlegal.com

Before joining Cogent Legal as the Executive Director of the Seattle office, Tyler Weaver was a partner at Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP in Seattle, where he oversaw the day-to-day litigation of complex cases in a wide array of subject areas (intellectual property, consumer protection, civil rights, securities, and antitrust, to name just a few). Tyler brings more than 16 years of litigation experience to Cogent and is uniquely qualified to assist you in crafting a persuasive narrative punctuated by cogent visuals.