My goal is to never create an image for my clients that they cannot use. As a former litigator, I understand that creating a beautiful, concise, compelling image is only half the battle – you still have to be able to use it. And for that reason, we here at Cogent Legal know the law that governs the admission of the images we create, and we share it with you.

In this latest series of posts, I discuss the relevant law in federal courts. For the general rules, see Part One. In this concluding Part Two, we address a few specific issues our clients commonly encounter, and some tips for avoiding those issues. And finally we conclude some advice on why you should think about your demonstrative exhibits as early in your case as possible.

Common issues with demonstrative evidence you should consider.

There are a few evidentiary issues that we see arise fairly frequently with our clients that we try to work on with them at the very start of our engagements. Those issues have to do with foundation, hearsay, and the point at which lawyers start using visuals in their cases.

- Hearsay is still hearsay if it is in a demonstrative exhibit.

Inadmissible hearsay does not become admissible simply because you have a nice summary of it. If you want to use documents in a timeline, for example, those documents must be independently admissible. Exceptions to the hearsay rule that our clients often find helpful include: the exemption for admissions by an opposing party or its representatives (FRE 801(d)(2)); the business records exception (FRE 803(6)); the ability of an expert to rely on otherwise inadmissible hearsay (FRE 703; see, e.g., U.S. v. Mejia, 545 F.3d 179, 197-98 (2nd Cir. 2008)) and the exception for previous sworn testimony by an unavailable witness (FRE 804(b)(1)). And you should always consider whether you can argue that you are not using a particular statement for its truth (and thus it is not hearsay). FRE 801(c).

- You may need to lay a foundation for your demonstrative evidence

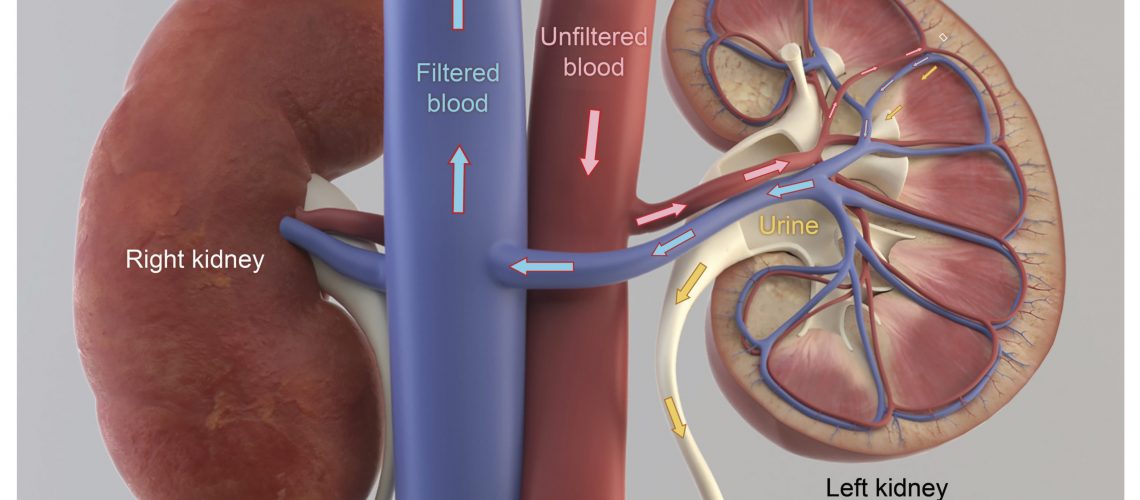

In addition to ensuring that your demonstrative evidence in founded on admissible evidence, you may also need to lay a foundation for the demonstrative evidence itself. This is especially important when your demonstrative is a depiction of an event, a place, or a condition.

In many cases, this is not complicated. A photograph, illustration, video, or animation can be authenticated by a witness with knowledge of what the evidence is depicting. FRE 901(a), 901(b)(1). This is often someone who was at the scene that is being depicted at the time being depicted, or by the person who created or designed the visual, but it can also be someone who can testify that they recognize the scene or place even if they were not there at the relevant time and did not create it. See, e.g., U.S. v. Clayton, 643 F.3d 1071, 1074 (5th Cir. 1981) (“A witness qualifying a photograph need not be the photographer or see the picture taken; it is sufficient if he recognizes and identifies the object depicted and testifies that the photograph fairly and correctly represents it.”); U.S. v. Holmquist, 36 F.3d 154, 169 (1st Cir. 1981).

Depending on the evidence at issue, you may need an expert to authenticate that the visual is an accurate depiction of the expert’s opinion. For example, a demonstrative demonstrating an internal injury might need a medical expert to support it. And an animation of an accident that had no nonparty witnesses or videotape might need an accident reconstruction expert to support it. See, e.g., Burchfield, 636 F.3d at 1336-37 (video recreation excluded because no witness testifed that the accident conditions were substantially similar to the recreation). There is no hard and fast rule, as who you can call (and who you want to call) will vary from case to case, but you should keep in mind who will testify as to the accuracy of the demonstrative evidence. And if you hire Cogent, we have vast experience dealing with these issues.

- There are some separate rules to keep in mind for documents that summarize other evidence.

There are a couple of additional wrinkles to keep in mind if the demonstrative you are using is a summary of other evidence in the case, such as a table summarizing testimony or documents. If the summary is for illustrative purposes only, the standards are the same as for all types of demonstrative evidence. The summary needs only to be based on admissible evidence, and a “sufficiently accurate and reliable” summary of that evidence, even if it contains inferences drawn by the party seeking to admit it. See, e.g., Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 398; Bray, 139 F.3d at 1111; Janati, 374 F.3d at 273.

However, a different standard applies if you seek to introduce a summary of documents that are too voluminous to bring into evidence otherwise. In that case, the summary is a substitution for other evidence, and must meet the requirements of FRE 1006. For these sorts of summaries, you must demonstrate that the summary is the only practicable way of presenting the evidence, the underlying documents have been provided to the opposing party and would be admissible, and the summary would assist the jury in understanding what is in the voluminous records. See, e.g., Bray, 139 F.3d at 1112; Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 396-98.

Don’t wait until the last minute to create your demonstrative evidence.

All too often, we see that the biggest hurdle our clients face is that they did not think about their demonstrative evidence until a few days before trial. We can, and do, help people who come to us very late in the process, but there are many reasons to address this situation sooner.

The most obvious reason is that you will have better demonstrative evidence that is more integrated into your case if you are working on it well in advance of the time you need it. It will be more accurate and it will be more compelling.

Another key consideration is that if you have at least a rough of your visual exhibits early, you may be able to start defining the case on your terms by using your visual representation at depositions and hearings. This forces people to react to your narrative, and either agree with it or indicate specifically what they dispute.

Along the same lines, you can use your demonstrative evidence strategically to avoid last-minute challenges. For example, consider the case of medical-injury animation supported by an expert. If the expert includes the animation with her written report, and is subject to a deposition on it, the less likely it is that the opposing party will be able to claim an element of unfair surprise or prejudice. Even more important, the expert can adjust the animation before trial to address any valid criticism. All this strategic leverage is gone if demonstrative evidence is put off until the last minute.

And while some attorneys are attracted by the potential shock value of having demonstrative evidence appear for the first time at trial, we often find that quality demonstrative evidence works well to drive settlement or win big pre-trial motions. It not only shows the seriousness with which you are taking the case, but also forces the other side (and any judge or mediator) to seriously consider your client’s perspective.

You can reach Tyler Weaver at 206.816.5128 and tyler.weaver@cogentlegal.com. Tyler brings more than 16 years of litigation experience to Cogent. Before joining Cogent Legal as the Executive Director of the Seattle office, he was a partner at Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP in Seattle, where he oversaw the day-to-day litigation of complex cases in a wide array of subject areas (intellectual property, consumer protection, civil rights, securities, and antitrust, to name just a few).