Relevance, Hearsay, and Foundation

Here at Cogent Legal, we create visuals that help you tell your client’s story as clearly and persuasively as possible. But as former litigators, we also understand that creating the visuals is only part of the battle – you also need to be able to use them. We continually ask ourselves not only what we can do to make your visuals as compelling and beautiful as possible, but also what we can do to make sure they are admitted.

We also like to assist our clients in understanding how they will be able to use their exhibits, so that they make this part of their overall strategy. So we periodically publish guides on the relevant rules.

In this post, we focus on particular application of relevance, hearsay, and foundation that apply to demonstrative exhibits in Washington State courts. You will also want to review the earlier post on the general rules, and look for the upcoming Part Three: Experts, Summaries, and Using Visuals Early in Your Case.

The basic rules of evidence still apply to your demonstratives.

The standards for admitting demonstrative evidence are not onerous, but demonstrative evidence is only as good, and only as admissible, as the foundation on which it is built.

Even the snappiest visuals won’t allow you to skirt hearsay or relevance.

Demonstrative evidence is not exempt from the basic rules of evidence, and the rules that most commonly come into play are relevance and hearsay:

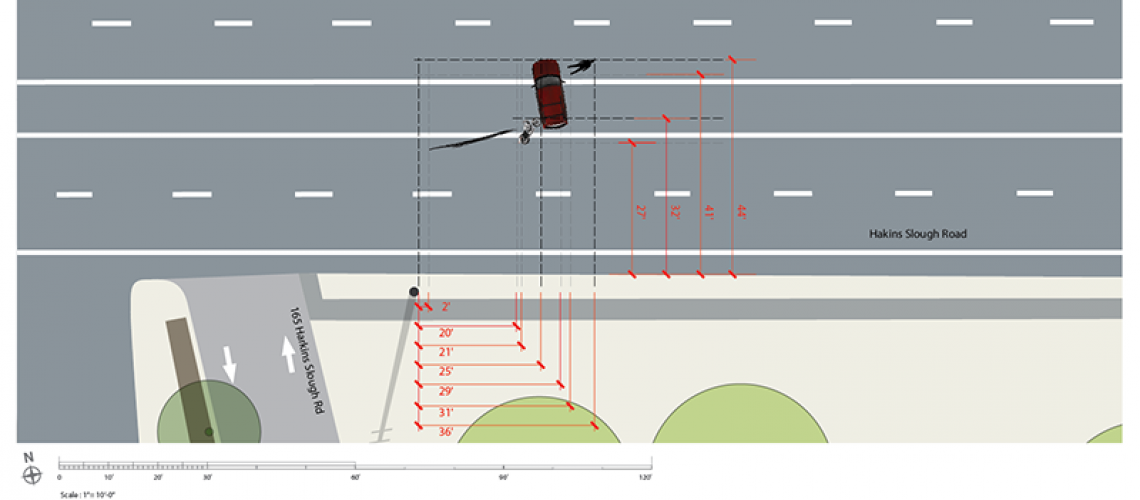

• Your demonstrative evidence has to be relevant, and that relevance cannot be outweighed by prejudicial effect. This seems simple, and it is if you are careful. The more closely your demonstrative evidence tracks the actual evidence it is illustrating, the more likely it is to be admitted. Animations or photos which exaggerate or misrepresent the conditions of a scene, for example, can have low probative value easily outweighed by the chance a jury would be misled.

For example, when a party sought to introduce a video “re-creation” of a killing, but that re-creation was done primarily by people who had not been at the scene and without expert assistance, and a witness to the original killing testified as to differences between the video and the actual event, the video was excluded due to a danger of unfair prejudice. See State v. Stockmyer, 920 P.2d 1201, 1203-05 (Wash. App. 1996).

Similarly, when an expert’s animation of a car accident sought to depict what would have happened under circumstances different than what actually occurred, that animation was excluded from evidence (and animations depicting what did occur were admitted). See State v. Hultenschmidt, 102 P.3d 192, 197-98 & n.7 (Wash. App. 2004).

They key is to have demonstratives that are accurate, and to support that accuracy with eyewitnesses, experts, or other witnesses who can establish accuracy of what you want to put before the jury.

• Hearsay is still hearsay if it is in a demonstrative exhibit. Inadmissible hearsay does not become admissible simply because you have a nice summary of it. If you want to use documents or other evidence in a timeline, for example, those documents or other evidence must be independently admissible. Exceptions to the hearsay rule that our clients usually find helpful: the exemption for admissions by an opposing party or its representatives (ER 801(d)(2)); the business records exception (RCW § 5.45.020); the ability of an expert to rely on otherwise inadmissible hearsay (ER 703; State v. Mohamed, 375 P.3d 1068, 1072-73 (Wash. 2016)) and the exception for previous sworn testimony by an unavailable witness (ER 804(b)(1)). And you should always consider whether you can argue that you are not using a particular statement for its truth (and thus it is not hearsay). ER 801(c).

You may need to lay additional foundation for your demonstratives.

In addition to ensuring that your demonstrative evidence in founded on admissible evidence, you may also need to lay a foundation for the demonstrative evidence itself. This is especially important when your demonstrative is a depiction of an event, place, or condition.

In many cases, this is not complicated. A photograph, illustration, video, or animation can be authenticated by a witness with knowledge of what the visual evidence is depicting. ER 901(a), 901(b)(1). This is often someone who was at the scene that is being depicted at the time being depicted, or by the person who created or designed the visual.[1] See, e.g., State v. Sapp, 332 P.3d 1058, 1061 (Wash. App. 2014); State v. Newman, 4 Wash. App. 588, 592-93 (1971).

In other cases, you may need an expert to authenticate that the visual is an accurate depiction of the expert’s opinion. For example, a demonstrative demonstrating an internal injury might need a medical expert to support it. An animation of an accident that had no witnesses or videotape might need an accident reconstruction expert to support it.

There is no hard and fast rule for setting a foundation, because who you can call (and who you want to call) will vary from case to case, but you should keep in mind who needs to testify as to the accuracy of the demonstrative evidence. And if you hire Cogent, we have vast experience dealing with these issues.

At Cogent Legal, we are ready to help you navigate these rules and get your demonstrative exhibits admitted at trial. Our goal is to never create a demonstrative exhibit that our client cannot use. You can reach Tyler Weaver, Executive Director of our Seattle office, at 206.816.5128 and tyler.weaver@cogentlegal.com

[1] It is worth noting that in some cases, visual evidence can be authenticated even without a witness testifying as to how it was made or when it was made, or even that the witness was there at the time being depicted. See Sapp, 332 P.3d at 1061-62. See also ER 901(b)(4). However, that typically requires circumstantial evidence such as where a photograph was found. Id. That extension of the rule is typically not relevant to demonstrative evidence created for a case.

Before joining Cogent Legal as the Executive Director of the Seattle office, Tyler Weaver was a partner at Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP in Seattle, where he oversaw the day-to-day litigation of complex cases in a wide array of subject areas (intellectual property, consumer protection, civil rights, securities, and antitrust, to name just a few). Tyler brings more than 16 years of litigation experience to Cogent and is uniquely qualified to assist you in crafting a persuasive narrative punctuated by cogent visuals.