Experts, Summaries, and Using Visuals Early

Here at Cogent Legal, we create visuals that help you tell your client’s story as clearly and persuasively as possible. But as former litigators, we also understand that creating the visuals is only part of the battle – you also need to be able to use them. We continually ask ourselves not only what we can do to make your visuals as compelling and beautiful as possible, but also what we can do to make sure they are admitted.

We also like to assist our clients in understanding how they will be able to use their exhibits, so that they make this part of their overall strategy. So we periodically publish guides on the relevant rules.

In this post, we focus on rules specific to demonstrative summaries, and the use of demonstratives as they relate to experts in Washington State courts. You may also want to review the earlier posts on the general rules and special considerations of relevance, hearsay, and foundation.

What to keep in mind regarding experts and demonstrative evidence.

There are some important rules to keep in mind regarding demonstrative evidence that is based on or related to expert testimony.

- If your demonstrative illustrates expert testimony, that expert testimony must itself be admissible.

Many demonstratives are designed to elucidate or enhance expert opinions. However, that expert and her opinion must be independently admissible for the demonstratives to be of any use. In Washington, the applicable standard is the one first used in Frye v. U.S., 293 F. 1013, 1014 (D.C. Cir. 1923). See, e.g., In re Detention of Throell, 72 P.3d 708, 724 (Wash. 2003) (“The Frye standard requires a trial court to determine whether a scientific theory or principle ‘has achieved general acceptance in the relevant scientific community’ before admitting it into evidence.”).

- If your expert is relying on a demonstrative exhibit, you’ll have to clear a higher hurdle

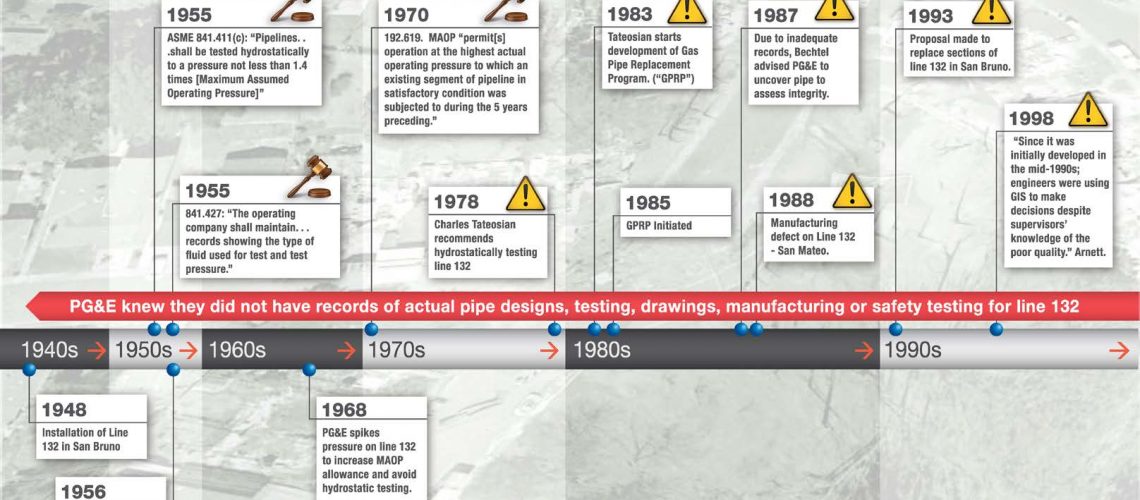

It is important to keep in mind that the higher Frye standard will also apply to any demonstrative exhibit an expert relies on to form her opinion, rather than simply uses to depict her opinion. Anything an expert creates that is offered as “substantive proof or as the basis for expert testimony regarding matters of substantive proof” will not be admitted absent evidence that the creation separately satisfies Frye. See State v. Sipin, 121 P.3d 111, 117 (Wash. App. 2005). This is a crucial difference, because if a demonstrative simply depicts the opinion, it must only meet the general rule requiring demonstratives to be relevant, and and not unfairly prejudicial.

In Sipin, for example, a defendant sought to admit a re-creation of an accident that had been created by inputting relevant data into a computer that created a simulation. The defendant’s expert then relied on that simulation to form an opinion about what happened. The simulation was ruled inadmissible because the program that created the simulation did not satisfy the Frye standard. See id. However, the court specifically indicated that the overall, lesser standard for demonstratives applied to animations that are used for illustrative, rather than substantive, purposes. See id., esp. citation of Contrast Commonwealth v. Serge, 58 Pa. D. & C. 4th 52 (2001). See also State v. Hultenschmidt, 102 P.3d 192, 197-98 & n.7 (Wash. App. 2004) (admitting accurate animations under lesser standard).

There are separate rules for documents summarizing other evidence.

There are a couple of additional wrinkles to keep in mind if the demonstrative you are using is a summary of other evidence in the case, such as a table summarizing testimony or documents. If the summary is for illustrative purposes only, the standards are not particularly different from that for other demonstratives. The summary needs only to be based on admissible evidence, and be a “substantially accurate” representation of that evidence. See State v. Lord, 117 Wash. 2d 829, 855-56 (1991); State v. Yates, 168 P.3d 359, 392 (Wash. 2007). The jury will receive a limiting instruction and will not be able to have the exhibit during deliberations. See Lord, 822 P.2d at 855-56.

However, a different standard applies if you seek to introduce a summary of documents that are too voluminous to bring into evidence otherwise. In that case, the summary is a substitution for other evidence, and must meet the requirements of ER 1006. For these sorts of summaries, you must demonstrate that the summary is the only practicable way of presenting the evidence, the underlying documents have been provided to the opposing party and would be admissible, and the summary would assist the jury in understanding what is in the voluminous records. See State v. Barnes, 932 P.2d 669, 683 (Wash. App. 1997). Cf. Matsushita Elec. Corp. v. Salopek, 57 Wash. App. 242, 248-49 (1990) (summary failed ER 1006 because records were not too voluminous, but it was properly admitted as a demonstrative exhibit).

Don’t wait until the last minute to think about demonstrative evidence.

All too often, the biggest hurdle our clients face is that they did not think about their demonstrative evidence until a few days before trial. We can, and do, help people who come to us late in the process, but we always urge our clients to think about their visuals much earlier in a case.

The most obvious reason is that you will have better demonstrative evidence that is more integrated into your case if you are working on it well in advance of the time you need it. It will be more accurate and it will be more compelling.

What is less obvious is that you can use your demonstrative evidence strategically so that you can avoid last-minute challenges. For example, consider the case of medical-injury animation supported by an expert. If the expert includes the animation with her written report, and is subject to a deposition on it, the less likely it is that the opposing party will be able to claim an element of unfair surprise or prejudice. Even more important, the expert can adjust the animation before trial to address any valid criticism. All this strategic leverage is gone if demonstrative evidence is put off until the last minute.

While some attorneys are attracted by the potential shock value of having demonstrative evidence appear for the first time at trial, we often find that quality demonstrative evidence helps to drive settlement and win big pre-trial motions. It not only shows the seriousness with which you are taking the case, but also forces the other side (and any judge or mediator) to seriously consider your client’s perspective.

At Cogent Legal, we are ready to help you navigate these rules and get your demonstrative exhibits admitted at trial. Our goal is to never create a demonstrative exhibit that our client cannot use. You can reach Tyler Weaver, Executive Director of our Seattle office, at 206.816.5128 and tyler.weaver@cogentlegal.com

Before joining Cogent Legal as the Executive Director of the Seattle office, Tyler Weaver was a partner at Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP in Seattle, where he oversaw the day-to-day litigation of complex cases in a wide array of subject areas (intellectual property, consumer protection, civil rights, securities, and antitrust, to name just a few). Tyler brings more than 16 years of litigation experience to Cogent and is uniquely qualified to assist you in crafting a persuasive narrative punctuated by cogent visuals.