My goal is to never create an image for my clients that they cannot use. As a former litigator, I understand that creating a beautiful, concise, compelling image is only half the battle – you still have to be able to use it. And for that reason, we here at Cogent Legal know the law that governs the admission of the images we create, and we share it with you.

In this latest series of posts, I discuss the relevant law in federal courts. This Part One summarizes the general concepts applied by federal courts, which are largely consistent with each other in their treatment of demonstrative evidence. In Part Two, I will discuss some special considerations regarding hearsay, foundation, and summary charts.

However, because there is no single leading case or rule in the federal courts, this is necessarily an overview. I have summarized the key concepts in these posts, but you should be sure to check for cases specific to the jurisdiction you are practicing in.

What is demonstrative evidence?

There is an important distinction between demonstrative evidence and foundational evidence. Different standards apply to these different types of evidence.

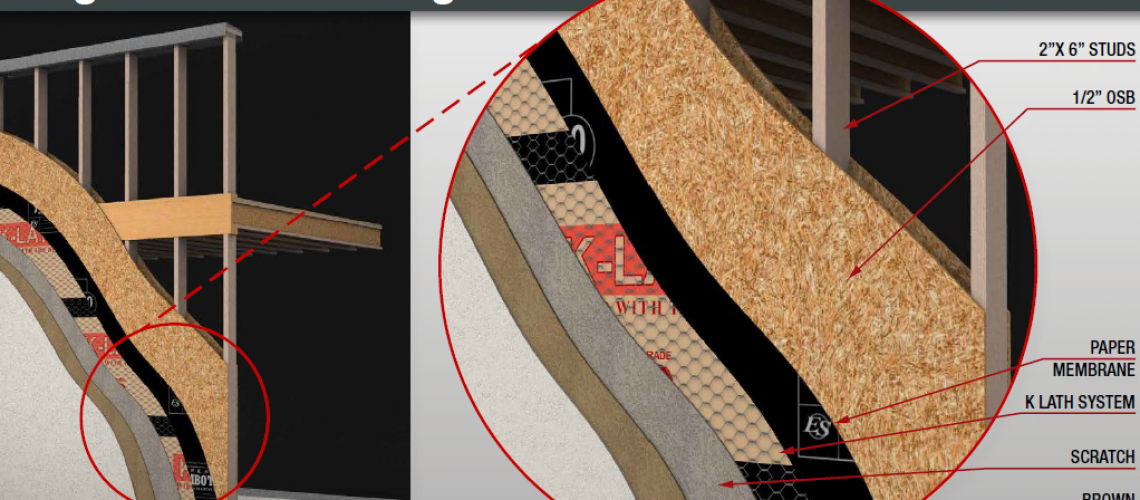

Generally speaking, demonstrative evidence is designed to “organize or aid the jury’s examination of testimony or documents which are themselves admitted into evidence.” U.S. v. Bray, 139 F.3d 1104, 1111 (6th Cir. 1998) (referring to such evidence as “pedagogical devices.”). This includes things such as diagrams, timelines, animations, summaries of already-admitted documents or testimony, and charts. Id.

It is important to keep the distinction between demonstrative evidence and foundational evidence in mind for at least two reasons. First, the general rule is that while the jury can view demonstrative evidence at trial, the demonstrative exhibits will not be available to the jury in deliberations and often come with a limiting instruction on their use. See id.. See also, e.g., U.S. v, Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d 390, 397, 398-399 (1st Cir. 2006); U.S. v. Taylor, 210 F.3d 311, 315 (5th Cir. 2000); U.S. v. White, 737 F.3d 1121, 1136 (7th Cir. 2013); Rogers v. Raymark Indus, 922 F.2d 1426, 1432 (9th Cir. 1991); U.S. v. Stiger, 413 F.3d 1185, 1198 (10th Cir, 2005); Robinson v. Mo. Pac. R. Co., 16 F.3d 1083, 1088 (10th Cir. 1994). But see, e.g., Bray, 139 F.3d at 1112 (demonstratives might be admitted into evidence if they are “so accurate and reliable a summary or extrapolation of testimonial or other evidence in the case as to reliably assist the factfinder….”); Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 398.

Second, courts tend to allow more flexibility in what can be portrayed or said in a demonstrative exhibit. As long as a demonstrative exhibit is relevant, admissible, and not in violation of FRE 403, it “may reflect to some extent … the inferences and conclusions drawn from the underlying evidence by the … proponent.” Bray, 139 F.3d at 1111. See also U.S. v, Janati, 374 F.3d 263, 273 (4th Cir. 2004); Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 398; White, 737 F.3d at 1135.

You also cannot prove a case with demonstrative evidence alone. But demonstrative evidence, done well, streamlines your case and makes it more compelling. Here’s what you should keep in mind to make sure you can use it in court.

Federal trial courts have broad discretion to admit (or exclude) demonstrative evidence.

As a general matter, trial courts have wide discretion to allow the use of demonstrative exhibits as “pedagogical” devices to assist the jury in understanding the case, in accordance with Fed. R. Evid. 611(a). See, e.g,, Taylor, 210 F.3d at 315; White, 737 F.3d at 1135; U.S. v . Gardner, 611 F.2d 770, 776 & n.3 (9th Cir, 1980); Stiger, 413 F.3d at 1197; Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 398; White, 737 F.3d at 1135; Byrd v. Guess, 137 F.3d 1126, 1135 (9th Cir. 1998).

Beyond that, while there is no single formula applied by the courts, the cases generally stand for the proposition that demonstrative evidence should be admitted if it is a reasonably accurate representation of the evidence it is based on, and its probity is not substantially outweighed by undue prejudice. See, e.g., Lies v. Farrell Lines, Inc., 641 F.2d 765, 773 (9th Cir. 1981) (“Where evidence is highly probative and it will not tend to prejudice or confuse the jury … all doubt should be resolved in favor of admissibility”); Taylor, 210 F.3d at 315-16 (“[a] necessary precondition to the admission of documents is that they accurately reflect the underlying records or testimony, particularly when they are based, in part, on … factual assumptions”); Burchfield v. CSX Transportation, Inc., 636 F.3d 1330, 1337 (11th Cir. 2011) (“experimental or demonstrative evidence, like any evidence offered at trial, should be excluded `if its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice, confusion of the issues, or misleading the jury.”); Bray, 139 F.3d at 1111; Milkiewicz, 470 F.3d at 399-400.

At least a couple of courts have directed trial courts to be particularly careful in admitting animations out of concern that an inaccurate or misleading animation can be unusually damaging. But even those decisions were decided on the general grounds of relevancy, accuracy, and probative value. See, e.g., Robinson, 16 F.3d at 1088 (“trial judges should carefully and meticulously examine proposed animation evidence for proper foundation, relevancy, and the potential for undue prejudice”); Fusco v. General Motors Corp., 11 F.3d 259, 263-64 (1st Cir. 1993) (affirming exclusion of an animation because the conditions depicted in it were not “substantially similar” to conditions at the time of the accident).

In many ways, this is simply common sense: your demonstrative evidence should be persuasive, but if they are a distortion of admitted documents or testimony, irrelevant, or minimally relevant yet highly prejudicial, you run a real risk that your exhibits will be excluded. You can avoid that if you are mindful of that situation upfront, as well as a few other common issues that come up.

You can reach Tyler Weaver at 206.816.5128 and tyler.weaver@cogentlegal.com. Tyler brings more than 16 years of litigation experience to Cogent. Before joining Cogent Legal as the Executive Director of the Seattle office, he was a partner at Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP in Seattle, where he oversaw the day-to-day litigation of complex cases in a wide array of subject areas (intellectual property, consumer protection, civil rights, securities, and antitrust, to name just a few).