Over the years, one of the most popular and well used items we have ever put out there is a simple, yet really helpful, net verdict calculator for personal injury cases under California law. This Excel sheet was originally created by my former law partner, Bob Arns, in the early 2000’s since he recognized two things: (1) it’s hard even for attorneys that calculate judgments all the time, which include workers’ compensation liens, to remember how to do it correctly; and (2) it’s close to impossible for anyone else, including courts that do not regularly deal with this specific issue often.

Since its conception in 2000, I’ve continued to update this Excel sheet to keep it current and refined. I decided recently to do another update (Beta Version) and share it with anyone interested, only asking that if any user identifies an error(s) or questionable results, please contact me to get it resolved. This is not simply a plaintiff or defense calculator; it is a tool that should accurately apply the law no matter what side you are on or regardless of your result.

I’m going to walk through a few of the bigger steps to explain them and how it works. First of all, any cell that is light blue can be filled out with your case specific numbers and names of the parties as indicated.

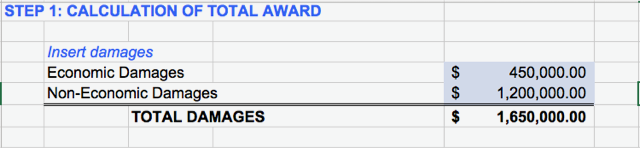

Step #1

Simply enter the total economic and non-economic awards. California law awards ALL economic damages regardless of fault jointly and severally, but non-economic damages are only awarded according to that parties specific fault. (See Civil Code §1431.2 and DaFonte v. Up-Right, Inc. (1992) 2 Cal.4th 593.)

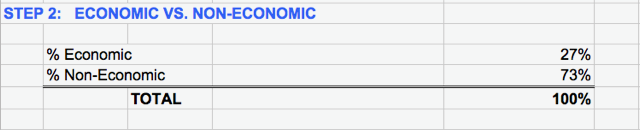

Step #2

Automatically performs the above calculation of the ratio between economic and non-economic damages.

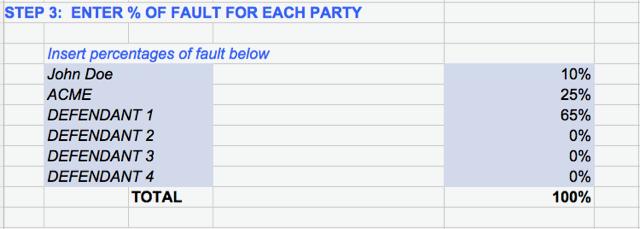

Step #3

Since a party is only responsible for their share of non-economic damages awarded, (see Civil Code §1431.2 and DaFonte v. Up-Right, Inc. (1992) 2 Cal.4th 593), each party needs to be identified, so the proper amount may be allocated. You may leave unused rows with the default text (0%). The result should always add up to 100%.

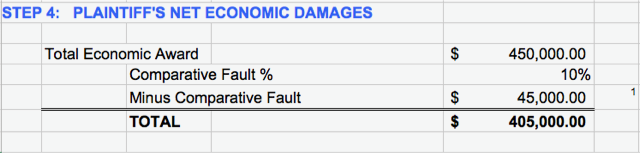

Step #4

Calculates the net economic award to plaintiff, which is the total award, minus the plaintiff’s own fault. This award may be obtained against any third-party defendant on the verdict form. (See Civil Code §1431.2 and DaFonte v. Up-Right, Inc. (1992) 2 Cal.4th 593.)

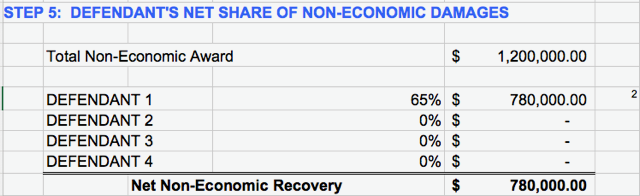

Step #5

Calculates the total non-economic award for each third-party defendant, based only on their percentage of fault finding, and this amount will be added to the judgment against them.

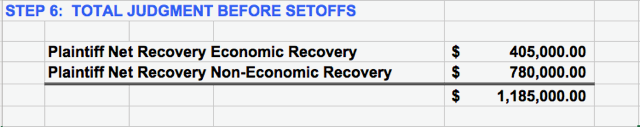

Step #6

We now have a net judgment. This was the easy part, but now we get into calculating the setoff for the workers’ compensation lien.

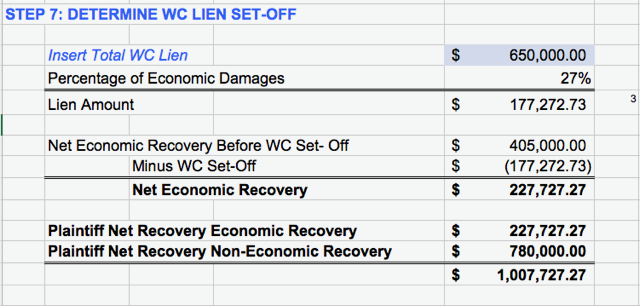

Step #7

Add the total workers’ compensation lien in the blue box, for all payments such as temporary disability, medical treatment, permanent disability and payments. The first calculation of Step #7 is from the case of Scalice v. Performance Cleaning Systems, 50 Cal.App.4th 221, which holds that since a workers’ compensation lien is comprised of some economic and non-economic elements, it should be treated the same as a prior settlement in the third-party case. Therefore, under Scalice, the overall percent of economic damages (27% in our example) is multiplied by the Total Lien Amount to get the setoff from plaintiff’s judgment to assure plaintiff does not receive a “double recovery.” But remember that a setoff from the judgment is different than whether a lien is actually owed or paid to the workers’ compensation carrier; this is addressed in Step #8.

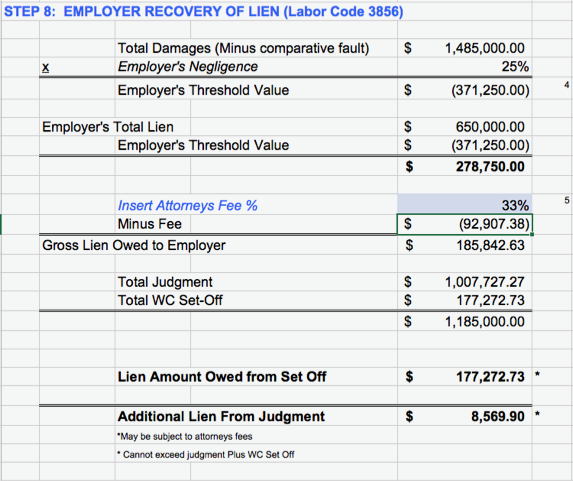

Step #8

This is the complicated one, but luckily this Excel sheet does all the math for you, other than adding in the reasonable attorney’s fees charged by the plaintiff attorney.

The key legal concept here is contained in Associated Construction & Engineering Co. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd., 22 Cal.3d 829, which holds that if an employer — who cannot be sued for personal injury in a civil lawsuit — is negligent in a manner that contributes to the injury, then the employer should not be allowed to recover their full workers’ compensation lien under equitable principles. Therefore, the TOTAL award (minus comparative fault) is multiplied by the employer’s finding of fault. This is known as the “threshold value”, under which the employer is not entitled to recover any lien. Here, the lien is still bigger than the threshold, so money is still owed back to the employer. If the total lien is lower than the threshold, no money is due back to the employer.

Next, the reasonable attorney’s fees are added to account for the work that the plaintiff attorney did to obtain the result and recover money for the employer. Under Summers v. Tice, et al., 33 Cal.2d 80 199; Labor Code § 3856, subd. (b), that percentage may be deducted from the lien amount. If the employer also has an attorney helping to recover money, it’s open to discussion on this issue depending on any value their counsel might have added.

After calculations, you get to the gross lien owed to employer, which is the amount of money that must be paid back to the employer from the judgment. Within the provided example, there is a “setoff” for the workers’ compensation lien within Step #7, there is a pot of $177,272.73 that may be used to pay the workers’ compensation lien with no further deductions from plaintiff’s judgment. In other words, since these funds were awarded to the plaintiff, but setoff to avoid the plaintiff getting paid twice for the same thing, any or all of these setoff funds can be used to satisfy the lien. However, when as in our example, there are insufficient funds to pay the entire lien from the setoff, the remainder must be taken from the plaintiff’s judgment.

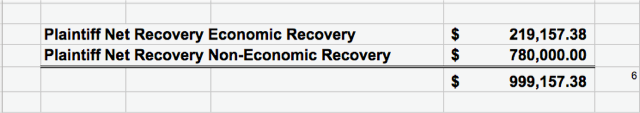

In an extreme example of a case where there is a relatively small recovery with a large lien and not much employer fault, you can get to a situation where the entire judgment is owed to the workers’ compensation carrier. (See Greathouse v. Amcord, Inc. (1995) 35 Cal.App.4th 831.) Based on the above example, with an large workers’ compensation lien, there is an additional $8,569.90 subtracted from the economic damages identified in Step #7 to arrive at the total net award.

The template proceeds to go through adding awarded costs, subtracting other liens and various other matters that may affect a judgment, but those are pretty self-explanatory.

We hope you find this Excel template valuable, and if you have any questions, or notice anything incorrect in the law or formula, please let us know. Since this Excel sheet is in a Beta form and provided free of cost, we at Cogent Legal take no responsibility for any errors in calculation or law and every user should confirm the law and math for their case.