A version of this article was first published in the January 2014 LexisNexis e-discovery brief.

A central case database where litigators track issues, witnesses, events, documents, to-do items and more is a vital tool for making e-discovery and litigation more efficient.

A central case database where litigators track issues, witnesses, events, documents, to-do items and more is a vital tool for making e-discovery and litigation more efficient.

While electronically stored information (ESI) is important, ESI rarely takes center stage in a closing argument. Rather, the attorneys will be telling the jury a story in closing argument—a story about the parties, what happened to bring those parties into court, and how the evidence before the jury supports the story. Although e-discovery may not be the star of the closing argument, it plays an important supporting role: the stories of closing will often be woven from threads first identified in e-discovery.

Thus, litigators reviewing e-discovery should be alert for elements of the story—e.g., what happened, who was there and why did it happen? Unfortunately, such key questions may be ignored or forgotten under the budget and deadline pressure of reviewing documents for responsiveness and privilege. What litigators need is a way to quickly capture nuggets of information for later analysis as they sift through the ESI.

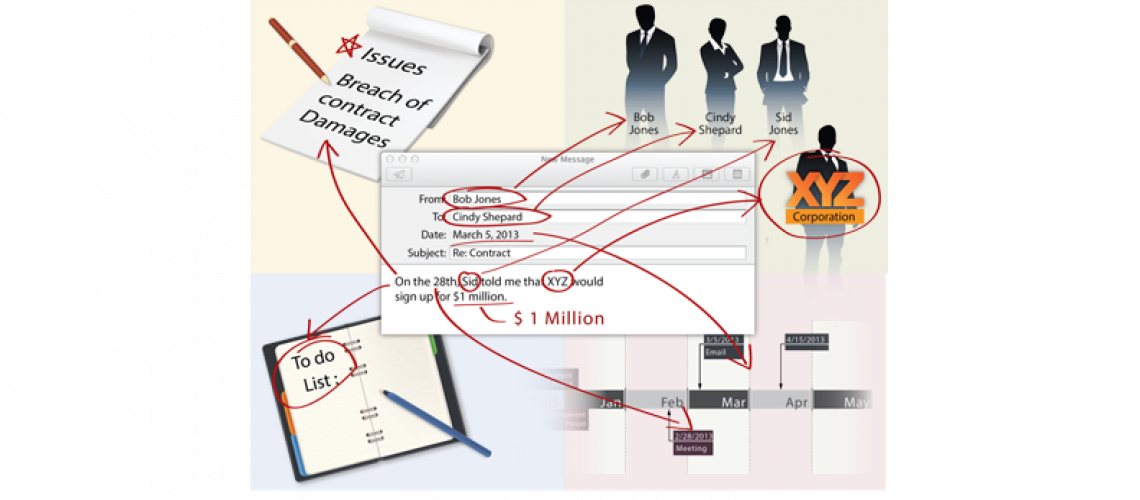

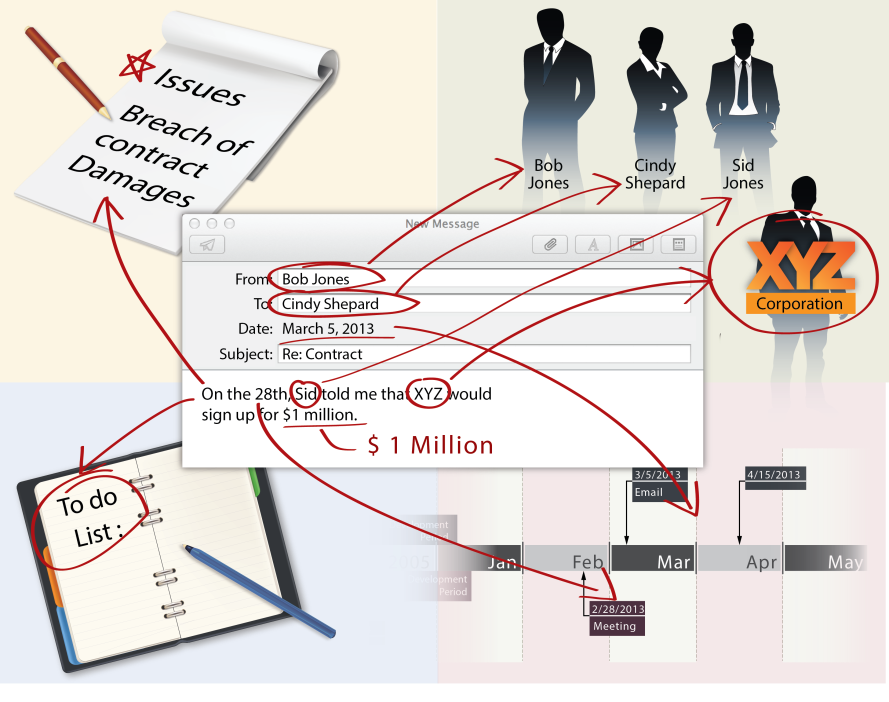

For example, Bob Jones may write an email on March 5 to Cindy Shepard about a meeting on February 28 where Sid Jones discussed a $1 million contract with XYZ Corp. This hypothetical email identifies three witnesses by name and implies perhaps at least a fourth witness from XYZ Corp. The email may also merit two different entries on a case chronology (the meeting date and the email date). A litigator may also want to link it to issues for breach of contract and damages. Perhaps most important, the email probably merits items on the team to-do list such as “Interview Bob Jones,” “Confirm “Sid” is Sid Jones” and “Discuss with damages expert.”

This hypothetical email and its interconnections demonstrate the need for a system that keeps track of many things at once. A relational database such as LexisNexis CaseMap case analysis software is the type of tool I prefer to meet this challenge. A case database lets you quickly link the email to each of the witnesses, issues and events, and quickly recall the information in a report or search. Moreover, as you learn more information (for example, perhaps in a deposition of Bob Jones), you can add to the information in the database linked to the original email.

A well-designed database allows the litigator to capture valuable thinking about the significance of a document without derailing the necessary high-speed workflow of ESI document review. For example, in our example of the hypothetical email, modern ESI document review software allows the litigator to send that document into the case database and capture the entries discussed above in the witness list, the issue list, the chronology and the to-do list. The link to the original documents may also be preserved so that one can go back and view the document and perhaps establish where it came from in the document production in case that becomes important for purposes such as laying a foundation.

Without a database, a litigator might try to maintain many spreadsheets, word processing documents or a very well tabbed notebook. However, such substitutes pale compared to a case database that provides search, filtering, sorting and reporting for a large team―all working simultaneously and perhaps in multiple offices or on the road.

Upcoming Webinar and More

If you’re interested in learning more about using case databases to manage ESI and other aspects of your litigation, you might want to attend a webinar that I will be giving on March 5, 2014, hosted by the Law Practice Management & Technology section of the California State Bar. The title of the webinar will be “Technology Tips for Using Databases to Understand, Develop and Control Your Case.”

For additional advice about e-discovery or case management and how Cogent Legal might be able to assist you, please contact me.

If you’d like to receive updates from this blog, please click to subscribe by email.