One of my first posts on this blog discussed all the complications involved with calculating a verdict in California for personal injury cases, especially when a workers’ compensation lien and/or prior settlement must be taken into account. Given my growing love of the iPad for litigation, I figured it was time to update that post and put my verdict calculator on the Apple program Numbers for iPad. (drumroll, please …) You can download the Numbers file directly to your iPad and work along with this post: Download Numbers Net Verdict Calculator. Please note, you will need a copy of Numbers on your iPad to view the file; it works best to open this post on your iPad, then click the download button, then choose “open in Numbers” from the icon at the top right of the screen.

One of my first posts on this blog discussed all the complications involved with calculating a verdict in California for personal injury cases, especially when a workers’ compensation lien and/or prior settlement must be taken into account. Given my growing love of the iPad for litigation, I figured it was time to update that post and put my verdict calculator on the Apple program Numbers for iPad. (drumroll, please …) You can download the Numbers file directly to your iPad and work along with this post: Download Numbers Net Verdict Calculator. Please note, you will need a copy of Numbers on your iPad to view the file; it works best to open this post on your iPad, then click the download button, then choose “open in Numbers” from the icon at the top right of the screen.

If you have not used Numbers on the iPad, I suggest the quick tutorial that comes with the app on the iPad to orient you to how it functions. Numbers is the Apple equivalent to Excel, but it is much more robust in its ability to make visually appealing graphs and charts.Let’s start with a little bit of background in calculating a verdict. In the days before Li v. Yellow Cab Co. (1975) 13 Cal.3d 804, the plaintiff received the entire award issued by the jury from any defendant that he or she chose to go after for the money, unless the plaintiff was partially responsible for the injury, in which case he/she received nothing. The rule was simple, but kind of harsh to both sides. For example, defendants with 1% fault could pay 100% of the award, and a plaintiff with only 1% responsibility for the injury would receive zero.

As with tax law, loophole upon loophole (and at least one ballot initiative) made the processes a great deal more complicated.What follows is a quick explanation of how these calculations were derived, with the “steps” corresponding to the steps on the worksheet. The sample shown below has numbers already included to show how the sheet functions, but if you download a copy of the file, you are free to put in whatever numbers you like. Just make sure to only put numbers in where it says “input” to the right of the box. The rest of the boxes are doing automatic calculations that are the same for any case. If you disagree with the calculations or have any other feedback, please leave a comment below.

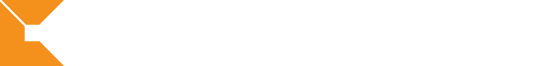

TAB 1 : TOTAL AWARD

Before the seminal case of Li v. Yellow Cab Co. (1975) 13 Cal.3d 804, a non-negligent plaintiff was allowed to recover the rest of his or her damages, whether economic or non-economic, from any defendant no matter the level of fault apportioned. However, any fault on the plaintiff’s part prevented any recovery from any defendant. Li got rid of the harsh comparative fault rules that prevented recovery with 1% of fault on the plaintiff, but left in place the common law rule that a plaintiff could recover any damages from any negligent defendant no matter how small that defendant’s own fault was found to be.

Proposition 51, which was codified as Civil Code § 1431.2(a), modified this common law rule, by limiting joint and several liability only to economic damages (i.e. plaintiff can ask any defendant for all of the plaintiff’s economic damages regardless of the level of fault of the defendant, but now non-economic damages were only awarded according to fault of that defendant).

Since percentages of fault determine the amount each defendant owes, the jury must make a finding on these issues and break down the award between economic and non-economic damages and percent of fault for each party, and this number is placed into this tab. As you can see from the screen shot below, I have added in graphs that visualize each tab that change whenever the information is amended.

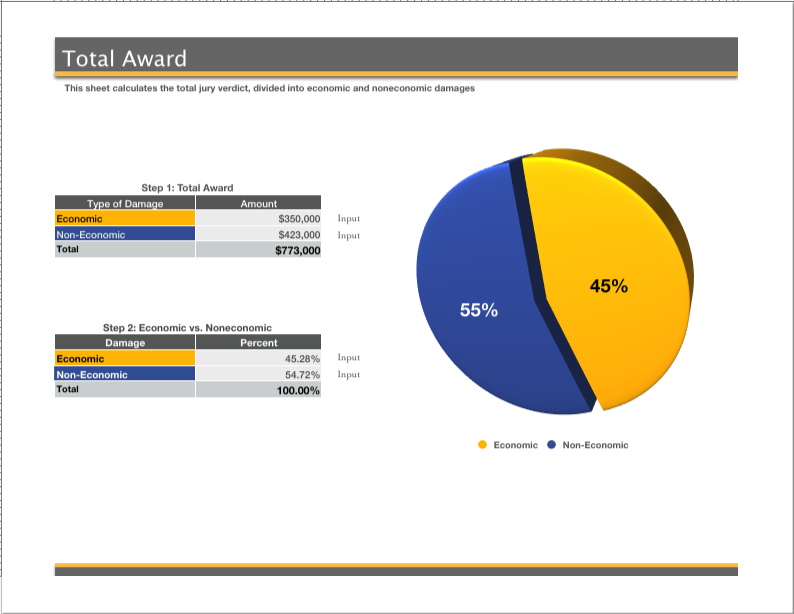

TAB 2: FAULT

Under Torres v. Xomox Corp. (1996) 49 Cal.App.4th 1, and Civil Code Section 1431.2, the plaintiff’s comparative fault is subtracted from the economic award off the top. Therefore, you must determine the percentage of economic to non-economic and subtract plaintiff’s fault from the economic component only. The non-economic are handled later.

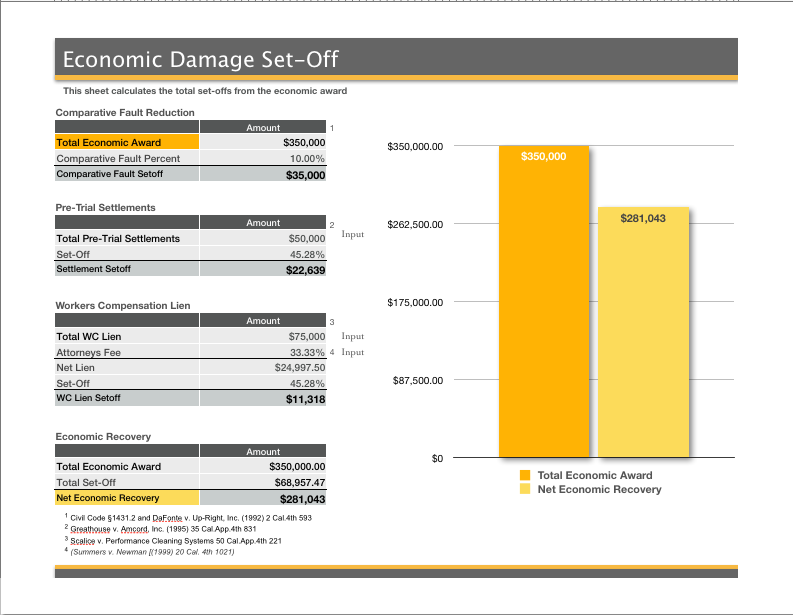

TAB 3: ECONOMIC REDUCTIONS

It seems like dealing with a pretrial settlement would be easy. If the jury awards total damages of $300,000 against all defendants, and one of the defendants already settled for $50,000, you would just subtract $50,000 from the $300,000, correct? Wrong.

Under Espinoza v. Machonga (1992) 9 Cal.App.4th 268, the court found that just like a verdict, a settlement has both an economic and non-economic component that are handled differently. Therefore, the economic part of any pretrial settlement is subtracted from the economic award to plaintiff after the comparative fault deduction. (See also Scalice v. Performance Cleaning Systems (1996) 50 Cal.App.4th 221.) Remember in regards to workers’ compensation liens that there is a set-off from the award no matter whether the employer is actually entitled to recovery in money on their lien, which will be determined in a later step (see Tab 6). Therefore, the economic part of any workers’ compensation lien is subtracted from the economic award. However, if the workers’ compensation carrier has not participated in the case, the plaintiff’s attorney is allowed to seek a reduction in the lien to account for their attorneys fees in recovering the lien for the workers’ compensation carrier. This section calculates that amount of reduction. (Summers v. Newman (1999) 20 Cal. 4th 1021)

TAB 4: NON-ECONOMIC DAMAGES

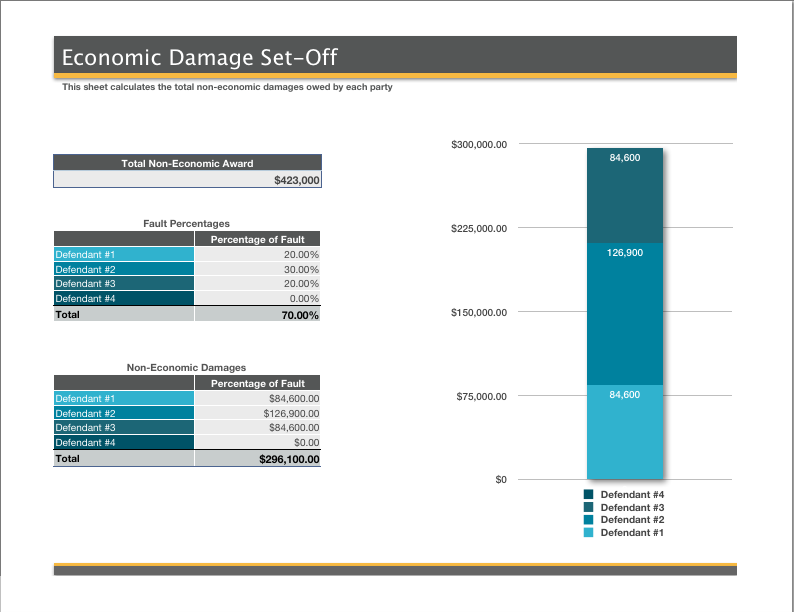

Under Da Fonte v. UpRight, Inc. (1992) 2 Cal.4th 593, interpreting Civil Code Sections 1431-1431.5, any defendant is only responsible for that share of non-economic damages (like pain and suffering) according to their specific finding of fault against them. However, they remain responsible for all economic losses regardless of who caused them so long as they are found 1% responsible. Therefore this page calculates the amount each defendant owes in non-economic damages.

TAB 5: NET AWARD BEFORE LIENS

This page adds together all the allowable recovery for the plaintiff as determined on the prior pages.

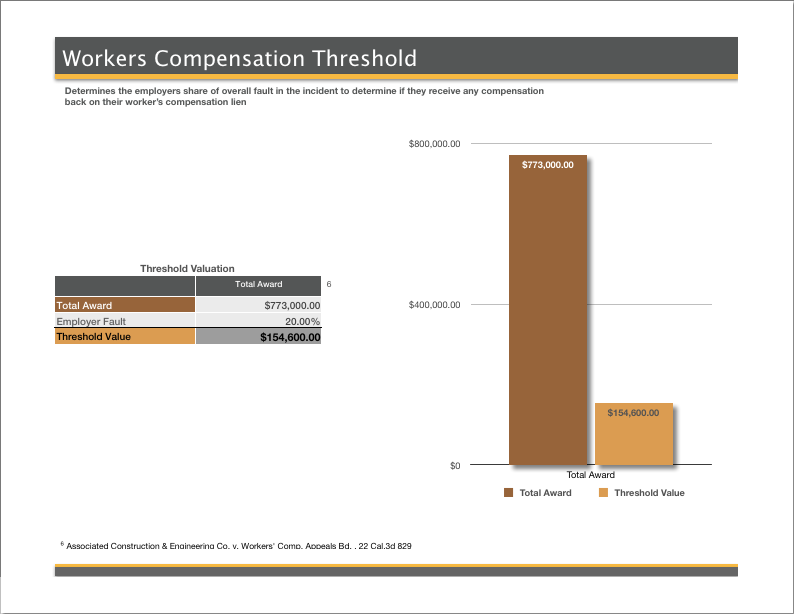

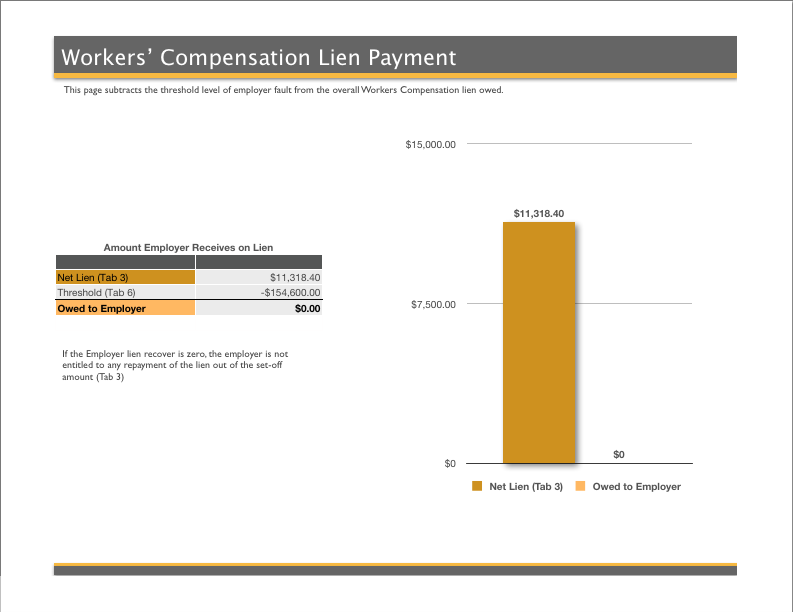

TABS 6-7: WORKERS’ COMPENSATION LIEN REPAYMENT

This is the confusing one. When a workers’ compensation lien exists, one not only calculates set-off (see Tab 3) but also the amount of repayment that the workers’ compensation carrier gets back, if any. The formula to determine the “threshold level” is set forth in Associated Construction & Engineering Co. v. Workers’ Comp. Appeals Bd. (1978) 22 Cal.3d 829, 843. In short, the employer gets nothing back from the amount set-off from the verdict until after the “threshold” number of their personal fault multiplied by the total damages is reached. This prevents a negligent employer from recovering for their own negligence.

I hope this summary and the downloadable Numbers file will help you figure out the trial value of a case with all the additions and subtractions that go into the current state of the law for calculating such recoveries. (If you would like the original Excel version of this Net Verdict Calculator, please click here.)

If you have any questions on the calculation of a Net Verdict in California, I’m happy to talk to you about it; just contact me.

If you appreciated this blog post, please nominate Cogent Legal Blog before Sept. 7, 2012, for the ABA’s Top 100 “Blawg” List; click here and input the URL https://cogentlegal.com on the form to nominate this blog.